Older Adults’ Perceptions about Methodologies Used to Learn English as a Foreign Language

Percepciones de adultos mayores sobre metodologías utilizadas para aprender inglés como lengua extranjera

Percepções de idosos sobre metodologias utilizadas para aprender inglês como língua estrangeira

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2025.16.2.4022

Cecilia

Cisterna Zenteno

Universidad de

Concepción

Chile

cecisterna@udec.cl

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9707-154X

Marcela

Cabrera Abarza

Universidad de

Concepción

Chile

mcabrera@udec.cl

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0511-2908

Ignacio

Roa Herrera

Universidad de

Concepción

Chile

igroa2018@udec.cl

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-1873-0640

Received:

12/07/24

Approved:

03/11/25

How

to cite:

Cisterna Zenteno, C., Cabrera Abarza, M., & Roa

Herrera, I. (2025). Older adults’ perceptions about methodologies

used to learn English as a foreign language. Cuadernos

de Investigación Educativa,

16(2).

https://doi.org/10.18861/cied.2025.16.2.4022

Abstract

Older adults' increased longevity and improved health are becoming a great achievement in this century. In lifelong learning, active learners in the community benefit from a variety of courses offered by different institutions, with foreign language learning showing particular positive effects on emotional and mental health. Teaching a foreign language to older adults requires teachers to use specific approaches and effective strategies. The main aim of the following study was to analyze older adults' perceptions of the teaching methodologies for learning English in terms of activity types, resources, approaches, and motivations to learn the language. A convenience sample of 24 participants who attended English classes at a Chilean university was selected. This descriptive-quantitative study collected data using a Likert scale survey, highlighting key trends and patterns derived from participants' experiences in a shared educational setting. Data analysis included measures of central tendency and word cloud analysis. The results showed that older adult learners appreciate socially interactive English lessons that involve sharing experiences; they enjoy using audiovisual resources but find listening and reading skills challenging due to limited vocabulary and age-related hearing impairments.

Keywords: older adults, English language learning, foreign language, teaching methodologies, language skills.

Resumen

Hoy en día, el aumento de la longevidad y la mejora de la salud de los adultos mayores se está convirtiendo en un gran logro de este siglo. En el aprendizaje permanente, los estudiantes activos de la comunidad se benefician de una variedad de cursos ofrecidos por las instituciones, y el aprendizaje de idiomas muestra efectos particularmente positivos en la salud emocional y mental. La enseñanza de una lengua extranjera a adultos mayores requiere que los docentes utilicen metodologías especiales. El objetivo principal del siguiente estudio fue analizar las percepciones de los adultos mayores sobre metodologías de enseñanza para aprender inglés en términos de tipos de actividades, recursos, enfoques y motivaciones para aprender el idioma. Se seleccionó una muestra por conveniencia de 24 participantes que asistían a clases de inglés en una universidad chilena. Este estudio descriptivo-cuantitativo recopiló datos mediante una encuesta de escala Likert, destacando tendencias y patrones clave derivados de las experiencias de los participantes en un entorno educativo compartido. Para analizar los datos se utilizaron medidas de tendencia central y análisis de nube de palabras. Los resultados mostraron que los estudiantes adultos mayores aprecian las lecciones de inglés socialmente interactivas que implican compartir experiencias. Les gusta usar recursos audiovisuales, pero les resulta difícil escuchar y leer, debido al vocabulario limitado y las deficiencias auditivas relacionadas con la edad.

Palabras clave: adultos mayores, aprendizaje del inglés, lengua extranjera, métodos de enseñanza, habilidades lingüísticas.

Resumo

Hoje em dia, o aumento da longevidade e a melhoria da saúde dos idosos representam uma grande conquista deste século. No contexto de aprendizagem ao longo da vida, os estudantes ativos da comunidade se beneficiam com a variedade de cursos oferecidos pelas instituições, sendo o aprendizado de idiomas especialmente positivo para a saúde emocional e mental. Ensinar uma língua estrangeira a idosos exige o uso de metodologias específicas por parte dos professores. O principal objetivo do presente estudo foi analisar as percepções de idosos sobre metodologias de ensino de inglês, considerando os tipos de atividades, recursos, abordagens e motivações para o aprendizado do idioma. Foi selecionada uma amostra por conveniência composta por 24 participantes que frequentavam aulas de inglês em uma universidade chilena. Este estudo descritivo-quantitativo coletou dados por meio de uma pesquisa com a escala de Likert, destacando as principais tendências e padrões derivados das experiências dos participantes em um ambiente educacional compartilhado. Para a análise dos dados, foram utilizadas medidas de tendência central e análise de nuvem de palavras. Os resultados mostram que os estudantes idosos apreciam as aulas de inglês socialmente interativas, que envolvem o compartilhamento de experiências. Eles gostam de usar recursos audiovisuais, mas têm dificuldades na compreensão auditiva e de leitura devido ao vocabulário limitado e às deficiências auditivas relacionadas à idade.

Palavras-chave: idosos, aprendizagem de inglês, métodos de ensino, habilidades linguísticas.

Introduction

Countries worldwide are experiencing an aging population, with the proportion of older adults steadily rising due to increased life expectancy and lower fertility rates, as noted by Cursaru (2018). Advances in medicine and technology are significantly contributing to longer lifespans. The World Health Organization (2022) predicts that by 2050, the global population over 60 will double. In Chile, this demographic shift is already apparent, with rapid growth in the senior population. According to the Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2022), about one-third of Chile's population will be over 60 by 2050.

Defining elderly, older adults, or "third-aged" individuals is complex, as interpretations vary depending on the author or criteria applied (Gómez, 2008). Various definitions exist across research fields, with the most generally referring to retired individuals, typically around 60 to 65 (Great Senior Living, 2022). In Chile, the legal definition, according to Law No. 19.828, considers a person an older adult once they reach 60 years of age (Servicio Nacional del Adulto Mayor, SENAMA, n.d.).

The concept of active aging is gaining more relevance nowadays as today’s older adults have a different profile. They have a more active, independent lifestyle and want to be seen as individuals with unique experiences and higher expectations. The World Health Organization (WHO) has highlighted the new opportunities and challenges that global aging presents to individuals and societies (WHO, 2024). Today’s older adults are interested in learning about new subjects and have a wide range of opportunities as more institutions include activities, courses and workshops for them. Learning a foreign language is part of the new knowledge some older adults find interesting According to Klimova (2018), engaging in language learning not only stimulates cognitive processes but also promotes social interaction and mental health among older adults. It offers opportunities to connect with others, enhances brain flexibility, and provides a sense of purpose and daily engagement.

However, teaching English to older adults is an engaging field for educators; it presents significant challenges, as there is lack of specialized teaching methodologies, which highlights a significant gap in educational practices, requiring the development of tailored methods and approaches that account for their unique cognitive, social, and physical needs. There is scarce literature about which methods or strategies would be the most effective or what difficulties older adult learners face when learning a foreign language.

As a preliminary approach, the following study aims at analyzing a group of Chilean older adults' perceptions regarding the use of methodologies for learning English within a university setting, identifying the strategies they consider the most effective and the challenges they face in their learning process.

Literature

Review

Redefining

Older Adults and Expanding their Educational Opportunities

In today’s world, the rise in life expectancy allows older adults to stay active; they are willing to engage in activities that maintain their mental and physical well-being. As a result, in Chile, institutions like Universidad de Concepción, SENAMA (Servicio Nacional del Adulto Mayor), and Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile have created specialized programs for older adults, including courses in Art, ICTs, Psychology, History, Literature, and a variety of Language courses. Among them, language courses are particularly popular, fostering personal growth, cultural understanding, and professional opportunities.

A 2015 ADIMARK survey in Chile found that older adults save money mainly on holidays, traveling and meeting new cultures, favoring English-speaking countries to practice the language. They seek an active lifestyle, valuing new experiences and socializing. Their participation in language courses reflects an awareness of the importance of foreign languages for traveling and, for some, it is also important to stay connected with relatives abroad.

Additionally, older adult learners use English to navigate the internet for work, leisure, and staying connected. With global mobility, language skills help them socialize with friends and family living abroad and, most importantly, help them stay mentally active.

Foreign

Language Learning in the Third Age

As Gray (1999) states, the learning process of older adults differs from that of younger learners. This can be observed in the fact that they are known for being autonomous learners who can self-regulate and guide their learning process. Kuikka and Pulliainen (1995, as cited in Tukiainen, 2003) mention that senior’s spare time can be effectively used to promote their learning capacity and engagement in educational activities, including language learning.

Regarding motivation, as older adults have gone through a great number of experiences throughout their lives, they are highly motivated to take an active role in learning. Słowik-Krogulec (2017) notes that older adult beginners have clear personal motivations for learning a language, whether for recreational or occupational reasons. This drive enhances their success in language learning. They possess enriching experiences and a wide range of vocabulary, so they grasp complex concepts easily and can think critically about abstract ideas.

Therefore, it is essential for teachers to recognize, adapt, and consider the learning preferences of older adult students. This awareness helps teachers to tailor lessons to address these interests, which will ensure a more effective and rewarding learning experience.

Older adult learners are confident of their ability to develop learning strategies, aiding comprehension (Cozma, 2015). They are respectful, cooperative, and hardworking, making the teaching process really rewarding and gratifying (Donaghy, 2016). Teachers should go beyond games and songs, encouraging seniors to share experiences, goals, and reflections to deepen learning and connect new knowledge to their rich personal experiences.

In terms of the language learning process, Cox (2013) identifies four key areas in which older adults differ from other learners: sensory function, inhibitory control, working memory capacity (WMC), and processing speed (Park, 2000). The sensory function is crucial for processing auditory and visual information, inhibitory control helps them focus on relevant details while ignoring distractions, WMC is vital for maintaining information from multiple sources, and processing speed affects how quickly they can absorb and apply new information. The stereotype that older adults have problems retaining new information can increase anxiety in the learning process, which may negatively influence their performance (McDaniel et al., 2008). Considering these aspects, learning materials and classroom activities for older adults should be designed keeping these limitations in mind.

Teaching specific language skills to older adults requires tailored strategies. Listening comprehension is challenging due to rapid speech, unfamiliar voices, and classroom distractions. In general, this can be more challenging for older adults compared to younger learners. The cognitive load of tasks like reading while listening or exercises involving writing, matching, underlining, or marking correct answers adds difficulty, especially for the untrained ear of an older adult. Field (2008) highlights that decoding strategies are a major concern, especially for lower-level older adult students. Teachers should then apply targeted listening strategies to ease decoding and enhance comprehension, and specific strategies and materials should be chosen to meet older students' needs, ensuring engagement and success. Language activities should prioritize speaking, listening, and vocabulary, focusing on topics of interest to ensure a meaningful learning experience.

With retirement, seniors have more time to dedicate to language learning, allowing deeper focus and progress. While aging may slow responses or affect some mental functions, not all older learners are equally affected by memory decline or physical limitations. The Adult Education Program (2017) notes that they may simply need more time for tasks like writing and copying.

In some cases, these issues may be mild or even non-existent, while in other cases, they may be more pronounced and have a significant impact on learning. Kuikka and Pulliainen (1995, as cited in Tukiainen, 2003) highlight that the aging process in healthy adults does not typically lead to major memory changes, suggesting that memory retention in seniors can often remain stable, particularly when they maintain a healthy lifestyle. Kacetl and Klímová (2021) state that learning a foreign language can allow older adults to develop their cognitive skills and strengthen their emotional well-being. Despite age-related challenges, such as slower reaction times and, in some cases, memory difficulties, older adults possess a remarkable ability to acquire and retain knowledge. Cozma (2015) emphasizes that the knowledge seniors acquire tends to be long-lasting and stored in their long-term memory, making it a solid foundation for further learning.

In the social domain, learning a second language, such as English, can offer older adults the opportunity to expand their social circle and form new friendships. This, in turn, could help address loneliness, which affects 43.5% of older adults in Chile, according to the Quinta Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida en la Vejez (2019). By gaining the ability to communicate with more people, older adults can engage in more social interactions, fostering connections and combating feelings of isolation.

The cognitive benefits of language learning in older adults include delaying the onset of illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. According to the Glasgow Memory Clinic (2019), bilingual individuals possess greater cognitive reserves, which can help delay the onset of such diseases by approximately five years. Furthermore, Heredia and Altarriba (2014) suggest that older adults, as subordinate bilinguals (those who use their first language to learn a second), benefit significantly from grammatical awareness strategies when acquiring a foreign language.

Older adult students often feel insecure about their intellectual abilities due to aging, leading to concerns about declining skills (Cozma, 2015). They may avoid engaging in certain activities because they tend to feel embarrassed and prefer familiar strategies to new methods. These feelings of anxiety and frustration can create barriers to learning, making the educational process more challenging for them (Adult Education Program, 2017).

However, older adults possess strengths like free time, critical thinking, self-confidence, positive attitudes, and long-term retention, making them motivated learners. Memory and physical response issues vary among older adults, and many maintain strong cognitive functions when supported by suitable teaching methods.

Teaching

Older Learners: a Challenging Experience

Even though societies are rapidly aging, the learning needs of older adults remain under-addressed. Learning foreign languages ranks third in popularity for this group (Singleton & Ryan, 2004), but limited research on teaching approaches, strategies, and techniques creates challenges for English teachers.

Adults have strengths such as strong cognitive skills, self-direction, persistence, and motivation, which enhance language learning. However, they may also face challenges, such as becoming discouraged quickly and resistance to changing their established learning methods. The improper use of resources, reliance on subjective teaching theories, and lack of textbooks and materials adapted for older learners create challenges in teaching English to older adults. Although teachers may meet general educational needs, to some extent, many are not trained to teach older adult students and lack the specialized tools needed for creating an effective learning environment. Addressing these gaps is crucial for ensuring older adults' success in language learning.

The key challenge, then, lies in maximizing their strengths while minimizing the impact of these weaknesses. As Pawlak (2016) notes, teaching adults a foreign language presents various barriers, but it also offers numerous opportunities for growth and success. By adopting strategies that capitalize on their cognitive strengths and motivation, and simultaneously address potential obstacles, educators can maximize the effectiveness of adult language learning.

Methodology

and Participants

The following study adopts a descriptive-quantitative approach, aiming to analyze older adults' perceptions of the English teaching methodologies used by their teachers in the courses they were enrolled in. This design enables researchers to quantify perceptions and identify trends or patterns emerging from numerical data, making it well-suited for comparing older adults’ experiences in a shared educational context (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

The sample chosen for this study corresponds to a convenience sample of 24 older adults enrolled in three English courses offered at a school called EDHUARTE in a Chilean university. These participants, aged 60 years old or more, were retired and with a university degree. All of them attended 90-minute English lessons once a week for three months (12 classes, 24 hours in all), and their levels of English ranged from A1 level to B2 levels according to the Common European Framework of References.

The main criterion used for selecting these participants was the researchers’ easy access to the three English courses, as they were serving as the English teachers during the academic term. Taherdoost (2016) claims that convenience sampling is often chosen by researchers because they "select participants because they are often readily and easily available" (p. 22). No explicit exclusion criteria were established for participant selection; however, only students who completed the full course were included in the study, with the exception of those who withdrew for personal reasons.

The sample size was small (24 participants), limited to three English courses, which restricts the generalizability of the results to other similar contexts. Most participants held a university degree (95%) and were retired (87.5%), limiting the ability to explore the impact of the course on students with varying educational backgrounds or occupational profiles. Detailed information is provided in Table 1.

Table

1

Description

of participants

Instruments

The instrument used for the purpose of the study was a 4-point Likert paper-based scale survey (Matas, 2018) written in Spanish to assess the older learners' perceptions regarding the English teaching methodologies used by their professors in class. Sampieri et al. (2014) states that “a Likert scale consists of a set of items presented in the form of statements or judgments, to which participants are asked to react” (p.238). The Likert scale survey was validated by a sociologist and two experienced peer researchers, who have experience designing quantitative research instruments.

The survey consisted of 21 statements divided into five sections, and participants rated them using a four-point Likert scale: Totally Agree (4), Agree (3), Disagree (2), and Totally Disagree (1).

Section 1—Demographic data: Three assertions related to the participants’ age range, occupation, and level of schooling

Section 2—English teaching methodologies: Four items to assess perceptions about teaching methodologies, language skills, resources used in classes, and motivation to learn a language

Section 3—Language skills: Four statements assessed older adults' views about the four language skills.

Section 4—Use of resources: Four statements inquire about the resources and technology used in the English lessons (songs, games, role-plays, etc.).

Section 5—Motivation to learn English: Four assertions explored participants’ main interests to learn English (travelling, self-esteem, leisure, etc.)

Two open questions were included to examine the participants´ views of their own learning experiences related to aspects that could be enhanced in the English language course and opinions about the most complex teaching aspects perceived by the students during their learning process.

Procedures

The 4-point Likert scale survey was administered to older adult students in class by their professors to analyze their perceptions of various aspects of the teaching methodologies used in their English classes. The data analysis techniques used in this study were two: IBM SPSS Statistics 25 to create a database, and analyze the participants' responses. The data were converted into numerical variables for quantitative analysis, and mean value differences were examined to identify trends and patterns in their responses, facilitating comparisons across different aspects of English language learning among older adults, focusing on descriptive analysis. In the case of the two open questions, the responses were grouped according to the different topics addressed by the participants (Bryman, 2012). Following a content analysis approach (Krippendorff, 2018), each theme mentioned was considered an independent unit, allowing for a more accurate representation of the diversity of opinions expressed in the open-ended responses, rather than limiting the analysis to the 24 participants. The RStudio software was used to analyze the responses using the word cloud technique (Castillo & Saibel, 2018), adjusting the repetition of connectors, monosyllabic words, and word frequency to highlight frequent mentions. The analysis did not reveal significant variations considering the participants’ language proficiency levels; therefore, the responses were grouped collectively.

Ethical

Aspects

The voluntary response survey considered the anonymity of the study participants; they provided informed consent, and their information was kept confidential and used only for research, evaluation and course improvement purposes.

Results

The results of the study were analyzed based on the specific objectives defined for the study, which are presented below:

Specific objective 1: Inquire about the English language teaching methodologies that older adults perceive most appropriate.

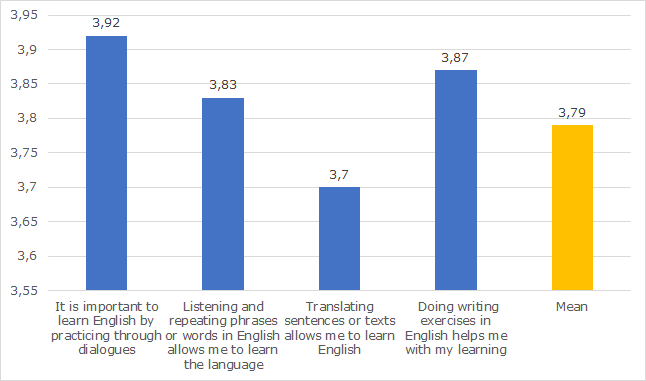

Table 2 and Figure 1 present information gathered about older learners' perceptions regarding English teaching methodologies.

Table

2

Perceptions

of English teaching methodologies among older adults

Figure

1

Older

adults’ perceptions about teaching methodologies used to learn

English

Analysis

of Section 1 of the Likert-scale survey shows that Statement 1 (It

is important to learn English by practicing through dialogues)

achieved the highest mean score (M = 3.92) and the lowest standard

deviation (SD = 0.282), with 91.7% of participants selecting Totally

Agree

as their response. The Agree

option accounted for 8.3% of responses. Overall, both responses

(Totally

Agree

and Agree)

indicated a highly positive perception regarding this aspect. This

result may be attributed to older adults' eagerness to communicate

and engage in communicative tasks, as maintaining social bonds

becomes increasingly important at this stage of life, reflecting the

social dimension of the learning process (Derenowski, 2021).

Regarding Statement 2 (Listening and repeating phrases or words in English allows me to learn the language), 100% of responses fell within the Totally Agree and Agree categories. According to Teaching English (n.d.), due to auditory decline, older adults benefit from activities that involve repeated listening to texts.

The lowest mean score (M = 3.7) and the highest standard deviation (SD = 0.470) were observed in Statement 3 (Translating sentences or texts allows me to learn English), indicating greater variability in participants' responses.

Finally, Statement 4 (Doing writing exercises in English helps me with my learning) received a combined 95.6% of Agree and Totally Agree responses. The overall standard deviation (SD = 0.4) and the high mean score (M = 3.79) reflect strong consensus among participants. Engaging in writing activities can be particularly beneficial for older adult learners, as it fosters self-direction and allows them to develop personal narratives or memoirs.

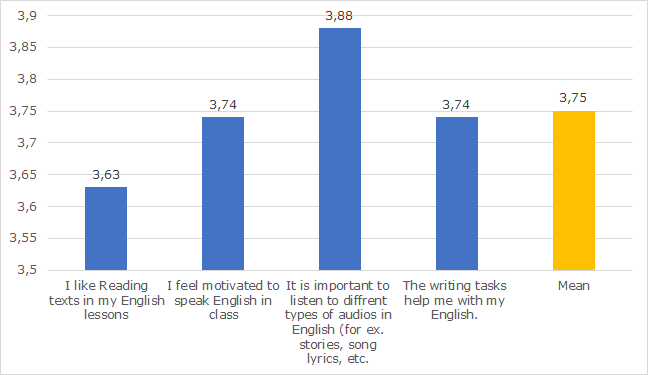

Specific Objective 2: To identify the language skills that older adults perceive as the most relevant when learning English. Table 3 and Figure 2 present the data collected on older adult learners' perceptions of language skills.

Table

3

Older

adult learners' perceptions of language skills

Figure

2

Older

adult learners’ perceptions of English language skills

Within this section, Statement 3 (It is important to listen to different types of audio in English, such as stories, songs, etc.) demonstrated the greatest consistency among participants, with 87.5% selecting Totally Agree and 12.5% selecting Agree, reflecting a highly positive trend. Older adult learners appear to value the use of diverse and authentic listening materials selected by their teachers during English lessons.

Statements 2 (I am motivated to speak in English during classes) and 4 (Writing texts in English helps me with the language) both recorded an identical mean score of M = 3.74. Most participants (70.8%) selected Totally Agree, while 25% chose Agree, indicating a positive perception overall. It is worth noting that both statements had one missing response. Older adults are often motivated to learn English for practical and personal reasons, such as improving communication with English-speaking family members, traveling abroad, accessing global information, or staying mentally active and engaged.

Finally, Statement 1 (I like to read texts in my English class) exhibited the greatest variability in participants´ responses. In this case, the percentage of Totally Agree responses decreased to 62.5%, while Agree responses accounted for 37.5%.

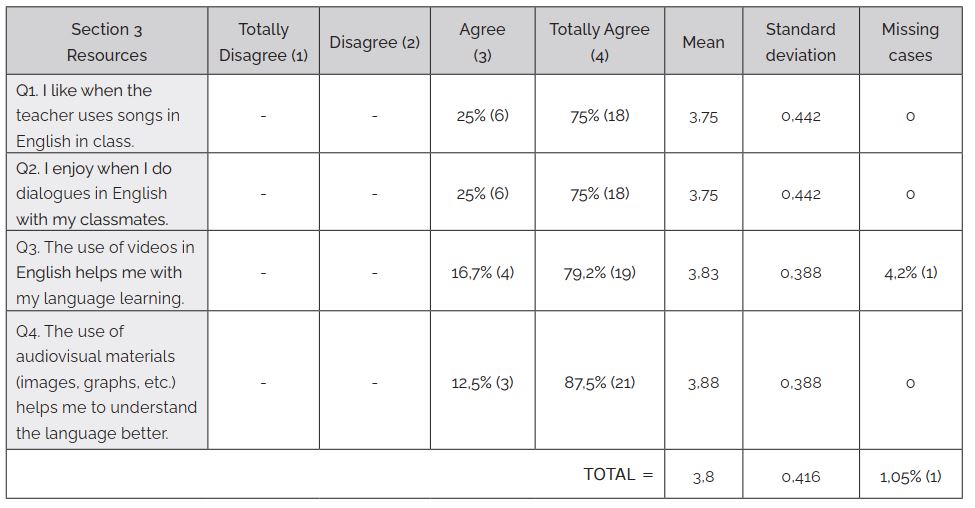

Specific

Objective 3:

To identify the most effective teaching resources for learning

English, as perceived by a group of older adults.

The data

collected from participants regarding this aspect are presented in

Table 4 and Figure 3.

Table

4

Older

adult learners’ perceptions regarding the use of teaching resources

to learn English

Figure

3

Older

adult learners’ perceptions about the use of teaching resources to

learn English

Within this section, Statement 4 (The use of visual materials, such as images or graphics, in English classes helps me to understand English better) showed the strongest consensus among the four statements, with 87.5% of participants selecting Totally Agree and 12.5% selecting Agree, and achieving the highest mean score (M = 3.88). The teachers in charge of the courses reported that using visual materials supported older adults' diverse learning styles by enhancing comprehension, memory retention, and engagement, and by making abstract concepts more concrete and easier to understand.

The second-highest mean score was observed in Statement 3 (The use of videos in English helps me with my learning), which achieved a combined 95.9% of positive responses (Totally Agree and Agree).

Statements 1 (I like when the teacher uses songs in class) and 2 (I enjoy when I take part in dialogues with my classmates) recorded identical mean scores (M = 3.75) and standard deviations (SD = 0.388), with responses concentrated in the Totally Agree and Agree categories. Participants commented that they particularly enjoyed activities that provided practical, real-life communication practice within a supportive environment. They felt their confidence improved and made the learning process more enjoyable, reducing anxiety about speaking in a new language.

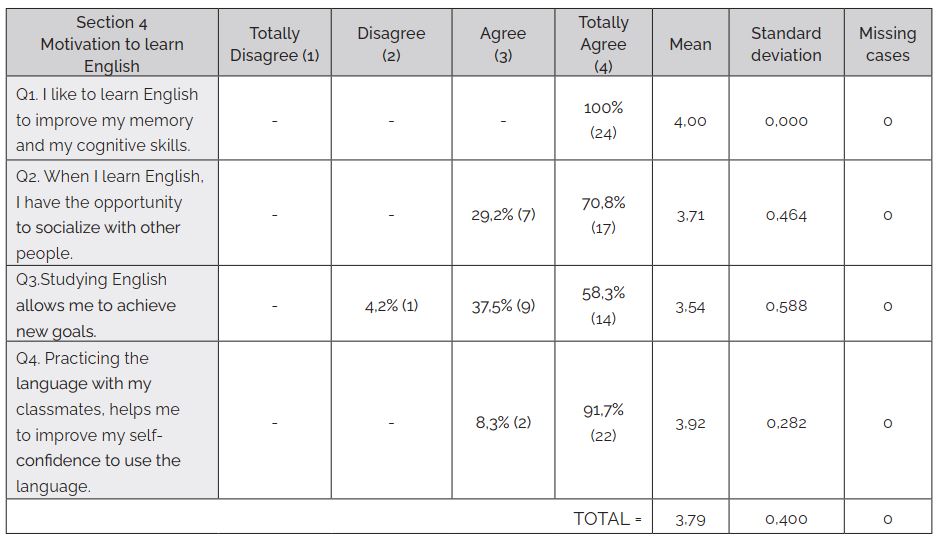

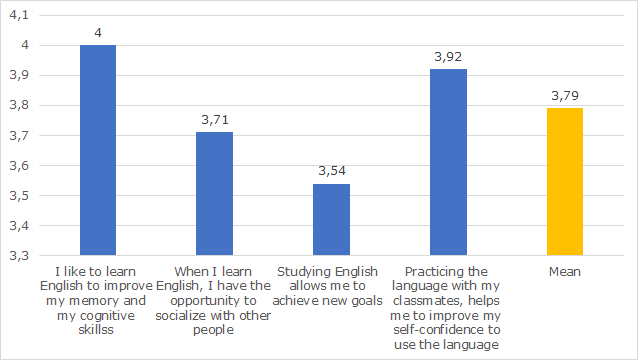

Specific Objective 4: To analyze the motivation that older students have to learn English as a second language.

The participants’ survey responses regarding this aspect are presented in Table 5 and Figure 4.

Table

5

Older

adult learners’ perceptions about their motivation to learn English

Figure

4

Older

adult learners ´perceptions related to their motivation to learn

English

Within this section, regarding the option Totally Agree, Statement 1 (I like to learn English to enhance my memory and cognitive skills) stood out, reaching 100%, followed by Statement 4 (Practicing the language with my classmates improves my confidence in using English) with 91.7%. The low standard deviations indicate a highly homogeneous population. Another important overall percentage in the Totally Agree/Agree options was found in Statement 2 (When learning English I have the opportunity to socialize with other people), which recorded a high mean (M = 3.71) and a low standard deviation (SD = 0.464). The teachers of English remarked that learning English helped their older adult students develop social bonds by enabling them to communicate with a wide range of people, fostering new friendships, and strengthening social connections. The lowest percentage was observed in Statement 3 (Studying English allows me to achieve new goals), with 58.3% of Totally Agree responses and 37.5% in the Agree option.

Analysis

of Participants´ Responses to the Open Questions

In the final section of the Likert scale survey, two open-ended questions were formulated in Spanish for the older adults to inquire about their learning experiences in the English course they had taken. The word cloud technique was used by the researchers to analyze their responses, as the data were qualitative. This technique is particularly useful for visually interpreting text and quickly gaining insight into the most prominent responses. In the survey, each response was analyzed separately as a case for participants who identified more than one theme, as reflected in the frequency data presented in Figures 6 and 8.

The questions were as follows: Question 1: What suggestion would you make to improve the English course and achieve better learning? and Question 2: What aspects of learning English were difficult for you to address during the semester?

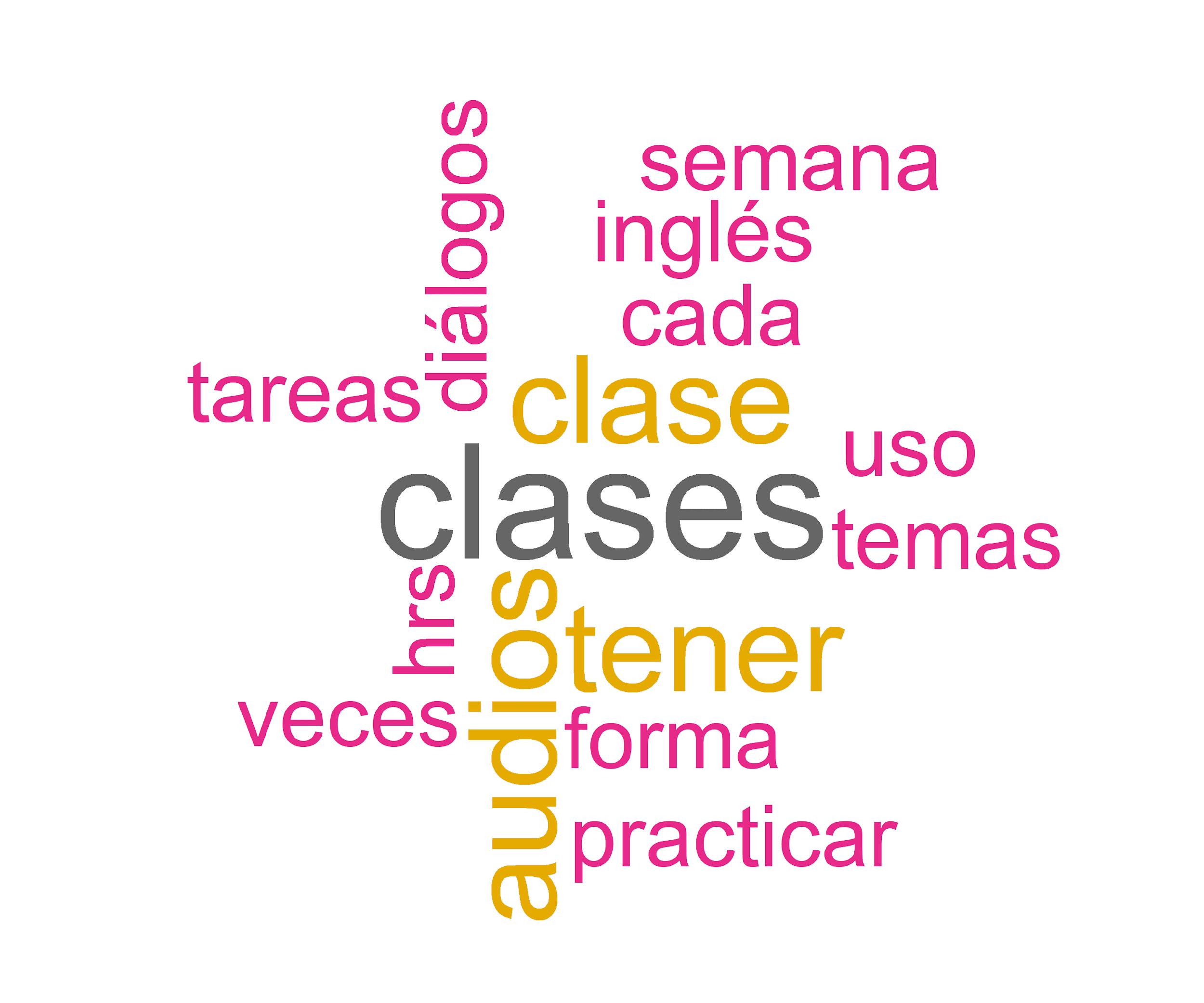

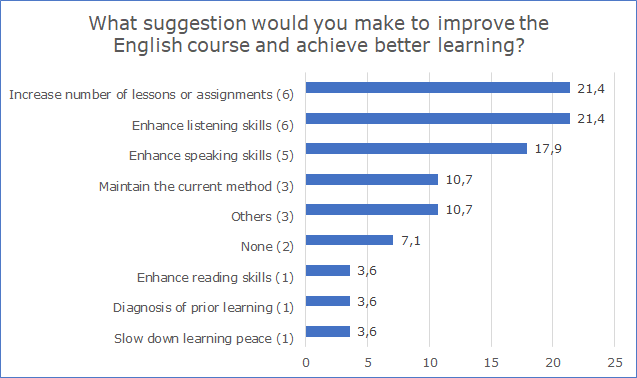

Older

adults’ responses to Question 1:

What

suggestion would you make to enhance the English course and achieve

better learning?

Participants´ responses analysis can be observed in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure

5

Older

adults’ suggestions to improve the English course

Figure

6

Older

adults' responses to Question 1

The main aspects (“highlighted words”) in the word cloud analysis were the following: having more English lessons during the week (participants currently had classes only once a week) and reinforcing the listening skill (21.4 responses). Enhancing the speaking skill was also highlighted (17.9) as a suggestion to make the English course better. The words featured in the word cloud, “diálogos” (n =2), “practicar” (n =2), were also consistent with the Likert scale responses given to statements such as: It is important to learn English by practicing through dialogues, or practicing the language with my classmates improves my confidence in using English. It is pertinent to mention that three participants indicated two topics in this question, increasing the total number of responses from 24 to 27.

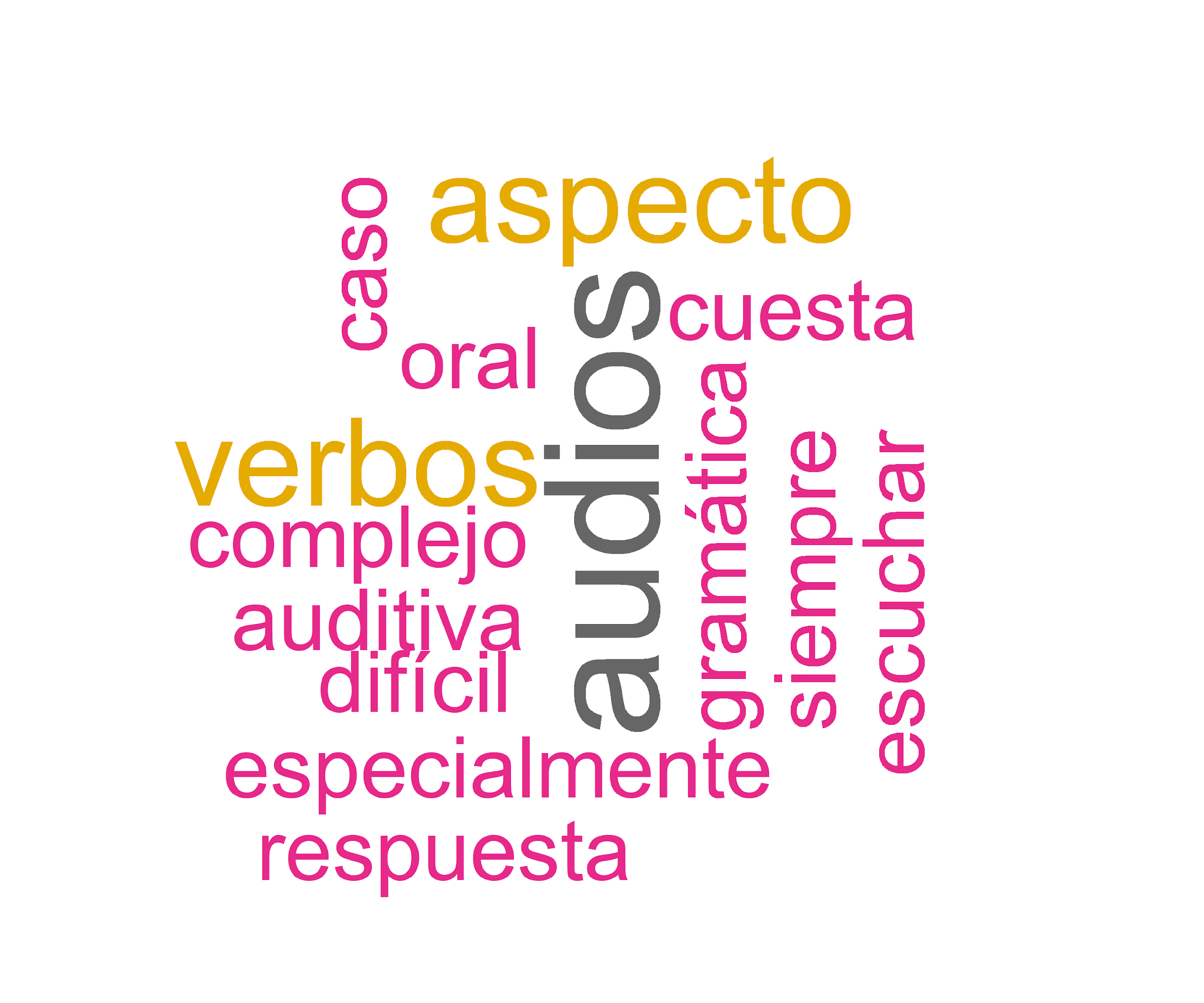

Older

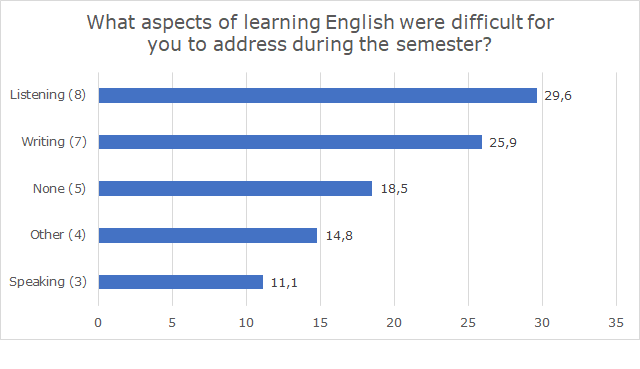

adult learners’ responses to Question 2:

What

aspects of learning English were difficult for you to address during

the semester?

Information about this question is presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8

Figure

7

Difficult

aspects older adult learners face when learning English

Figure

8

Difficulties

older adult learners face when learning English

The individual responses provided in the word cloud analysis, as well as the general results of the survey, showed several key insights regarding the central themes and feelings expressed about the main obstacles the participants found in the English courses they were enrolled. Among the four language skills, the listening skill (29.6) was underlined as a particularly complex skill. Prominent words such as “escuchar” (n = 2), “audios” (n = 4), “difícil” (n = 2), “complejo” (n = 2) exhibited the complexity this language skill involves. In the Likert scale survey, Statement 3: (It is important to listen to different types of audios in English, such as stories, songs, etc.), showed 87.5% of participants Totally Agreed and 12.5% Agreed that listening to various English audios was important, reflecting a strong positive trend despite age-related hearing decline. 25.9 participants also perceived writing as a challenge. Within this area, older adults commented on grammar aspects as the most complex, highlighting words such as verbs (n = 3), grammar (n = 2), and difficult. This finding does not fully align with the responses provided to Statement 4 (Writing texts in English helps me with the language), where 70.8% of participants selected Totally Agree and 25% selected Agree. Despite finding it difficult to memorize or practice grammar structures or to complete writing tasks, participants still recognized writing as a relevant exercise for learning English. In this respect, four participants pointed out two different themes, increasing the total number of responses from 24 to 28

Discussion

The present study aims to explore a group of Chilean older adults' perceptions regarding the use of methodologies for learning English within a university setting, identifying the strategies they perceive as most effective and the challenges they encounter in their learning process.

One main finding that emerged from this study underlined the fact that when teaching English to older adults, it is relevant for teachers to contextualize the learning situations using meaningful dialogues. In this aspect, the participants pointed out the importance of interacting with their peers when practicing the language, which may be linked to their need for socialization at this stage of life to keep their brains engaged. Kelly et al. (2017) indicate that individuals need frequent contact and support from others, and this affects positively their cognitive functioning. This opinion was reflected in the statement "It is important to learn English by practicing through dialogues" (M = 3.92). Older adult learners tend to feel anxious at the time of learning a new language. For this reason, designing activities that involve working in pairs helps them to reduce this level of anxiety. Atma (2018) indicates that teachers should create a friendly atmosphere with suitable classroom activities free from anxiety to make students feel comfortable speaking English.

Another interesting idea mentioned by this group of older adult learners was related to the use of technologies (ICT) in their English lessons, including multimedia tools such as videos and images that facilitate understanding. Older adult students’ responses were very concise in the survey, especially in Statement 3 (The use of audiovisual materials, such as images and graphs, helps me to understand the language better) (M = 3.88), and in Statement 4 (The use of videos in English helps me with my language learning) (M = 3.83). Bull and Ma (2001) state that technology offers unlimited resources to language learners. Additionally, Solanki and Shyamlee (2012) and Pourhosein Gilakjani (2017) reaffirm that the use of technology satisfies both the visual and auditory senses of learners. This aspect is particularly relevant, given that this group of learners exhibits diverse learning styles.

Some of the qualitative responses in the survey, regarding effective approaches or language skills older adult learners considered beneficial in the learning process, were reflected in the following comments: “The course is very good, the method used is very practical; you just have to be more consistent,” “The use of short videos with dialogues or with different information brochures, news, descriptions of characters, etc., is good to learn English,” “I would like to keep on reinforcing the language with different types of audios,” and “I like receiving emails with interactive homework with audios to practice the language.”

This suggests that interactive methods are not only effective but also perceived as necessary in English lessons to increase motivation and sustain learning progress. Consistent with Határ and Grofčíková (2016), the communicative approach promotes more meaningful and applied learning, which is particularly relevant in the context of older adults, who tend to prefer real learning situations that allow them to apply their knowledge in practical ways.

In this study, the language skills that participants identified as presenting particular difficulties were listening and writing skills. In the case of writing skills, this difficulty could be associated with the cognitive complexity involved, particularly in terms of acquiring grammar rules, mastering syntax, and accessing lexical resources. Mahdi (2018) claimed that students often make mistakes when using verbs because teachers rely on traditional methods, which do not effectively help them learn grammatical rules. Although these older adult learners mentioned writing as a complex skill, they did not explicitly address this issue in the open-ended question regarding suggestions for course improvement. This is an area that could be explored in future research.

Listening skills were also perceived as challenging, mainly due to hearing loss associated with aging. A study conducted by Kuklewicz and King (2018) found that acquiring proficient listening abilities posed a significant obstacle for elderly individuals learning English as a foreign language (EFL). This finding suggests that teachers should select, for example, textbook activities featuring contextualized listening tasks with slow and clear audio recordings, storytelling activities, videos with subtitles, and pair work discussions to make students feel at ease and reduce potential frustration.

In terms of speaking skills, older learners commented that lack of vocabulary was an obstacle for them. One participant reflected this concern by stating, "The lack of vocabulary makes it difficult, for example, to ask questions, in my case, with very basic English." Considering this comment, it is suggested to include speaking activities to encourage communication, build confidence, and address their unique learning needs. Dialogues and role-playing situations can help older adults practice the language authentically in a safe and supportive environment.

However, it is important to highlight in this study that, despite the difficulties mentioned by older adult students, they demonstrated resilience and interest in improving their listening skills, as reflected in Statement 3 (Listening to different types of audios in English helps me) (M = 3.88). One student commented, "I have always had difficulty in the listening part, but as the classes progressed, the progress I made in this aspect was noticeable." According to Wilson (2008), teachers of older learners need to proceed more slowly with instructions, as the ability to cope with fast, connected speech tends to lag behind senior students’ cognitive abilities.

In reference to motivations, older adult learners identified cognitive enhancement and willingness to learn as the most important factors. Cognitive motivations play a central role in learning English among older adults. The statement I like to learn English to enhance my memory and cognitive skills (M = 4.00) reached the maximum score, indicating that many students see learning a new language as an opportunity to strengthen their mental abilities. This finding aligns with studies suggesting that learning a second language contributes to the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's (Glasgow Memory Clinic, 2019). Furthermore, students' commitment and motivation to continue learning are evident in the responses provided to the open-ended questions in the survey, such as: "Let classes last longer or have classes two times a week." This desire to prolong learning sessions emphasizes an intrinsic motivation to take advantage of the available time and optimize the cognitive benefits of learning. The willingness to learn and motivation demonstrated by participants go beyond the academic context, reflecting an active pursuit of cognitive and social well-being.

In terms of the perceived usefulness of the English language among older adult learners, relevant aspects such as interaction and the social dimension of learning a new language emerged. Participants in this study emphasized the practical usefulness of English in their lives, extending beyond the academic context. Responses to the statements Practicing the language with my classmates improves my confidence in using English (M = 3.92) and By learning English I have the opportunity to socialize with other people (M = 3.71) indicated that classroom interaction enhances participants’ linguistic confidence. The interaction that develops between peers in conversation is highly effective and can lead L2 learners to focus on particular aspects of the context and on specific words in speech (Yu & Ballard, 2007).

As

older students focus on the social dimension of language, questions

arise regarding the usefulness of English outside the educational

context. The statement Studying

English allows me to achieve new goals

(M = 3.54) revealed greater variability in responses concerning

expectations about the use of the English language. Although some

participants viewed English as a tool to achieve personal goals,

others did not seem to project language learning as a means to

fulfill objectives beyond the classroom.

Older adult learners

may choose to learn a new language for enjoyment, to improve their

cognitive skills, or to meet new people. They are aware that engaging

in lifelong learning experiences can help them remain psychological

and cognitive health (Formosa, 2019). This finding raises important

questions about the broader motivations that older adult students

might have, and whether learning a foreign language addresses an

immediate need or rather reflects a desire for cognitive and social

self-realization.

Conclusions

This study focused on exploring a group of older adult learners’ perceptions of the methodologies used when learning English as a foreign language in a university setting. The main findings revealed that participants strongly prioritized the use of interactive methodologies and technology in English lessons. They also emphasized the importance of being exposed to pedagogical strategies that promote active participation and dynamic learning. Furthermore, they exhibited high levels of "motivation to acquire English due to its dominant position" (Pot et al., 2019, p. 8). Participants attended classes regularly once a week and indicated in the survey that they would like to have more lessons throughout the week. The main motivation these older learners highlighted appeared to be oriented primarily toward cognitive enhancement and mental well-being, rather than the immediate achievement of personal goals outside the classroom. Although the literature suggests that learning English in later life is often motivated by desires such as traveling and expanding social networks (ADIMARK, 2015), the results of this study reveal a somewhat different perspective regarding students' expectations and the practical application of the language in everyday life. This observation suggests the need to reconsider the real motivations that drive older students to learn English, moving beyond conventional goals.

In this context, educators interested in teaching English to older adults have a significant responsibility in selecting engaging activities that create a positive atmosphere and bring joy and entertainment to their senior learners. Older learners can perceive when "their teachers are respectful, supportive, well organized, and positive" (Dewaele et al., 2019, p. 4). The use of videos, visual materials, and role-playing situations is perceived as fundamental to achieving an effective learning process. Klímová and Pikhart (2020, p. 3) state that some "more experienced teachers choose activities like group discussions, reading, playing games, watching YouTube videos, or singing in a foreign language." In this sense, it is important to reflect on the need to create multisensory learning experiences that support both students’ linguistic development and social interaction within the classroom. These results align with previous research highlighting the importance of meaningful and contextualized learning for older learners (Határ & Grofčíková, 2016).

However, it cannot be ignored that older adult learners face certain difficulties throughout their learning process. In this study, grasping some grammar structures and acquiring new vocabulary proved to be particularly challenging for the older students, partly because the groups were not always homogeneous and included individuals with different learning styles and preferences. For example, senior students often struggle to apply tenses correctly and require instruction within real-life contexts. In the word cloud analysis, participants clearly expressed that this process was difficult for them. Ali et al. (2021) claims that students often use tenses inappropriately when referring to permanent present situations.

Undoubtedly, the cognitive barrier represents a significant challenge that senior learners must face as neuroplasticity declines with age. However, in this study, participants demonstrated remarkable resilience in overcoming barriers, particularly in tasks such as listening comprehension. Difficulties in reading and listening skills highlight the need to develop future interventions aimed at improving educators’ teaching practices to better support these areas, as well as the necessity to create specialized didactic resources for older learners. There is a clear need for specialized textbooks for teaching English to older adult learners—materials specifically designed to meet their unique learning needs and characteristics.

In conclusion, older adult students appreciate opportunities for interaction and meaningful learning in the classroom. Future English language teaching programs for older adults should focus on strengthening the connection between language learning and its applicability in social and functional contexts beyond the classroom, integrating activities that more clearly address students' personal expectations and everyday needs. Such an approach would maximize the impact of English learning in both cognitive and social terms, responding more effectively to the particularities of this age group.

Despite the limitations of this study, particularly regarding the small sample size, the results provide valuable contributions to the literature on education for older adults. The study offers insights into a specific profile of older learners—retirees with higher education—whose perceptions may inform improvements in English course methodologies, the identification of specific language skills to be prioritized, the selection of appropriate learning activities, and future comparative research involving older adult populations with different educational backgrounds or occupational profiles.

Final

approval of the article:

Verónica

Zorrilla de San Martín, PhD, Editor in Charge of the journal.

Authorship

contribution:

Cecilia

Cisterna Zenteno: conceptualization, data curation, research,

methodology, supervision, resource management, visualization, writing

of the draft and review of the manuscript.

Marcela Cabrera

Abarza: research, writing of the draft and review of the

manuscript.

Ignacio Roa Herrera: data curation, formal analysis,

research, software, visualization, writing of the draft and review of

the manuscript.

Availability

of data:

The

data and figures generated, organized according to the corresponding

program, are available at the following Drive

link.

References

Adult Education Program. (2017). Meeting the needs of adults. https://wvde.state.wv.us/abe/tcher_handbook_pdf/section3.pdf

Ali, S., Ali, I., & Hussain, S. (2021). Difficulties in the Applications of Tenses Faced by ESL Learners. Research Journal of Social Sciences and Economics Review, 2(1), 428-435. https://doi.org/10.36902/rjsser-vol2-iss1-2021(428-435)

Atma, N. (2018). Teachers’ Role In Reducing Students’ English Speaking Anxiety Based On Students’ Perspectives. Asian EFL Journal, 20(7), 42-51.

Bull, S., & Ma, Y. (2001). Raising learner awareness of language learning strategies in situations of limited recourses. Interactive Learning Environments, 9(2), 171 -200. https://doi.org/10.1076/ilee.9.2.171.7439

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Castillo, F., & Saibel, C. (2016). Nubes de palabras animadas para la visualización de información textual de Publicaciones Académicas. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11818/615

Cozma, M. (2015). The challenge of Teaching English to Adult Learners in Today’s World. Procedia, 197, 1209-1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.380

Cox, J. (2013). Older adult learners and SLA: Age in a new light. In C. Sanz & L. Beatriz (Eds.), Issues in language program direction (pp. 90–107). AAUSC.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Cursaru, A. (2018). What are the main causes of population aging and its consequences on the provision of healthcare? https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.26511.23204

Dewaele, J.M. (2019). The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on willingness to communicate among English foreign language learners. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 38(4), 423–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X19864996

Donaghy, K. (2016). How to Maximize the Language Learning of Senior Learners. British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/how-maximise-language-learning-senior-learners

Formosa, M. (2019). Active ageing through lifelong learning: The University of the Third Age. In M. Formosa (Ed.), The University of the Third Age and Active Ageing (pp. 3-18). Springer.

Field, J. (2008). Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge UP.

Glasgow Memory Clinic. (2019). Can learning a language help prevent dementia? https://neuroclin.com/learning-language-prevent-dementia/

Gómez, M. (2008). El aprendizaje en la tercera edad. Una aproximación en la clase de ELE: los aprendientes mayores japoneses en el Instituto Cervantes de Tokio. Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. https://rb.gy/bbtr

Gray, H. (1999). Is there a theory of learning for older people? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 4(2), 195-200. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13596749900200054

Great Senior Living. (2022). Am I a senior citizen? Age, terminology, and what "old" really mean. https://www.greatseniorliving.com/articles/senior-citizen-age

Határ, C., & Grofčíková, S. (2016). Foreign language education of seniors. Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 4(2), 110–123. https://rb.gy/so6g

Heredia, R., & Altarriba, J. (2014). Foundations of bilingual memory. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9218-4

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C., & Baptista Lucio, M. P. (2014). Metodología de la Investigación. McGraw Hill.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. (2022). Cerca de un tercio de la población de Chile en 2050 estaría compuesta por personas mayores. https://rb.gy/pc8j

Kacetl, J., & Klímová, B. (2021). Third-age learners and approaches to language teaching. Education Sciences, 11(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070310

Kelly, M. E., Duff, H., Kelly, S., McHugh Power, J. E., Brennan, S., Lawlor, B. A., & Loughrey, D. G. (2017). The impact of social activities, social networks, social support, and social relationships on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0632-2

Klimova, B. (2018). Learning a foreign language: A review on recent findings about its effect on the enhancement of cognitive functions among healthy older individuals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00305

Klímová, B., & Pikhart, M. (2020). Current research on the impact of foreign language learning among healthy seniors on their cognitive functions from a positive psychology perspective: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 765. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00765

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Kuklewicz, A., & King, J. (2018). "It's never too late": A narrative inquiry of older Polish adults' English language learning experiences. TESL-EJ, 22(3), 1–22.

Mahdi, A. (2018). Difficulties in learning grammar: A study into the context of University of Technology, Department of Materials Engineering. Lark: Journal for Philosophy, Linguistics and Social Sciences, 1(31), 23–31.

Matas, A. (2018). Diseño del formato de escalas tipo Likert: un estado de la cuestión. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 20(1), 38-47.

McDaniel, M. A., Einstein, G. O., & Jacoby, L. L. (2008). New considerations in aging and memory: The glass may be half full. In F. I. M. Craik & T. A. Salthouse (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and aging (3rd ed., pp. 251–310). Psychology Press.

Park, D. C. (2000). The basic mechanisms accounting for age-related decline in cognitive function. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive aging: A primer (1st ed., pp. 3–21). Psychology Press.

Pawlak, M. (2016). Teaching foreign languages to adult learners: Issues, options, and opportunities. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum, 12, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.12775/ths.2015.00

Pot, A., Porkert, J., & Keijzer, M. (2019). The bidirectional in bilingual: Cognitive, social and linguistic effects of and on third-age language learning. Behavioral Sciences, 9(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9090098

Pourhosein Gilakjani, A. (2017). A review of the literature on the integration of technology into the learning and teaching of English language skills. International Journal of English Linguistics, 7(5), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v7n5p9

SENAMA (n.d.). Servicio Nacional del Adulto Mayor. http://www.senama.gob.cl/servicio-nacional-del-adulto-mayor

SENAMA (2019). Quinta Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida en la Vejez. https://rb.gy/m37t

Singleton, D., & Ryan, L. (2004). Language acquisition: The age factor (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Słowik-Krogulec, A. (2017). Teaching Listening Skills to Older Second Language Learners: The Students’ Perspective. Anglica Wratislaviensia, 55, 139-154. https://doi.org/10.19195/0301-7966.55.10

Solanki, D., & Shyamlee, M. P. (2012). Use of technology in English language teaching and learning: An analysis. In 2012 International Conference on Language, Medias and Culture (Vol. 33, pp. 150-156). IACSIT Press.

Taherdoost, H. (2016). Sampling methods in research methodology; how to choose a sampling technique for research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management, 5(2), pp. 18-27. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3205035

Tukiainen, K. (2003). A study on second language learning at an adult age - With focus on learner strategies [Master's thesis, University of Tampere]. University of Tampere Repository. https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/90751/gradu00207.pdf?sequence=1

Wilson, J.J. (2008). How to Teach Listening. Pearson Education.

World Health Organization. (2022). Ageing and Health. https://rb.gy/2t71

Yu, C., & Ballard, D. H. (2007). A unified model of early word learning: integrating statistical and social cues. Neurocomputing, 70, 2149–2165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2006.01.034